In a couple of months, a group of creative scholars, librarians, publishers, artists, and technologists will come together in Chapel Hill for four days for the first Scholarly Communication Institute to be held in the Research Triangle area of North Carolina, after a decade of SCI being held at the University of Virginia.

One of the issues we’ll be grappling with is how to connect the work of scholars with broader publics – not just in one direction (experts sharing what they know with other audiences) but also inviting and encouraging engagement of people from all walks of life in the creation and synthesis and understanding of useful knowledge together.

In an essay titled “Face the People and Speak” in Boom: A Journal of California last winter, Abby Smith Rumsey (convener and director of the former iteration of SCI at Virginia) wrote about her vision for a changing scholarly communication landscape:

In this world of proliferating arenas of expertise and specialization, we accept that we are, each and every one of us, “the general public” in all things except our own particular area of knowledge or skill. To the mycologist, a microbiologist is a layman, and to the expert on Leonardo da Vinci, the Nobelist in economics is at best an amateur in matters art historical. But, collectively, we advance knowledge and attend to the responsible use of that knowledge.

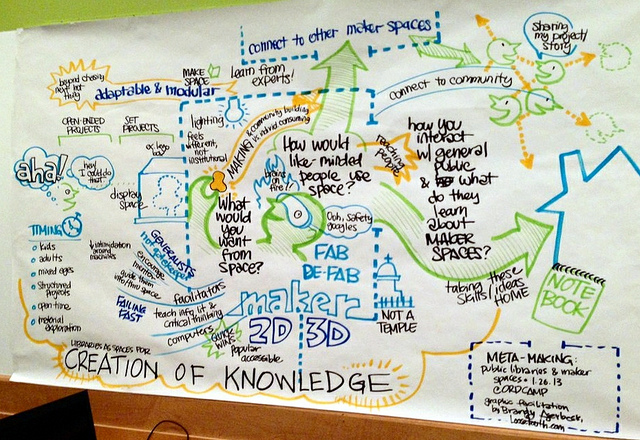

This year’s theme at the Triangle SCI is Scholarship and the Crowd, and participants will work on envisioning and building models for fostering and sustaining an ecosystem that is more catholic in its scope than what we usually think of when we hear the term “scholarly communication”.

It’s not just about peer reviewed journals, specialist conferences, and experts talking with other experts in narrowly defined disciplines. There is a global community of latent scholars – readers and writers and learners and thinkers; curators, data collectors, and people who are creating rich data sets of the human experience simply by leaving traces of their daily activities in the online spaces so many of us now frequent.

How do we help activate this richness, understand its opportunities, limitations, and constraints, and begin to develop norms to ensure that the benefits accrete into a commons shared by all, and don’t just accrue to an already privileged elite?

Rumsey writes:

It goes almost without saying that we shall have to find a new term for the work ahead, for “scholarly communication” fails to connote either the audiences for or the intentions behind this communication. I have been using the term “expert knowledge” in lieu of “scholarship” to acknowledge that information vital to our well-being is generated by many who are not traditionally considered scholars and that what is of greatest value is the knowledge that such experts create from raw information and data. Whatever term we embrace in the end, what matters is to focus equally on those who create and those who use knowledge. … The challenges and opportunities we will face in the coming decades will demand … humility, concern, and commitment to engage in translating expertise for multiple audiences and attending to the consequences of using knowledge responsibly.

Stay tuned. As the SCI transitions to the Triangle a new group is taking up this challenge. Together we’ll work to shape this broader meaning of “scholarly communication” and to build models that demonstrate it in practice.

[ Image credits: Communication by elycefeliz – https://www.flickr.com/photos/elycefeliz/3224486233 and World travel and communications recorded on Twitter by Eric Fischer – https://www.flickr.com/photos/walkingsf/6635655755 ]